This office gets calls all the time about the legal rights or prohibitions involving platted parks in subdivisions. Unfortunately, there are no easy answers. A new Court of Appeals decision highlights the issue.

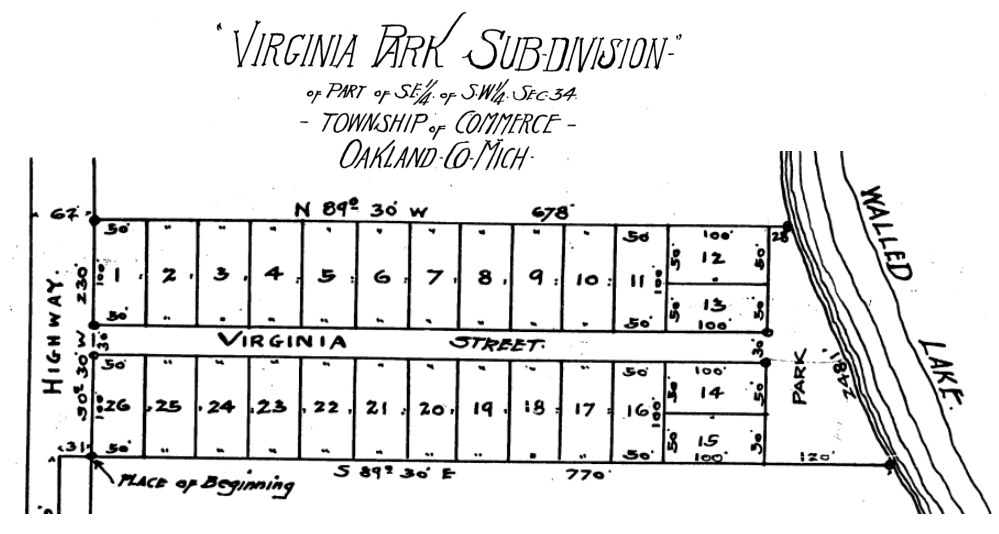

In Virginia Park Subdivision Association v Hair, the park-side lot owners had a dispute with the back-lot owners in the small subdivision on Walled Lake in Oakland County. The owners of Lots 12, 13, 14, and 15 claimed that the rest of subdivision could not use the park land to install docks and moor boats. The rest of the subdivision claimed equal rights.

The 1918 plat read that the “park as shown on said plat [is] hereby dedicated to the use of lot owners only.” It explains nothing more. Being a nearly 100 years old plat, the original creators of the subdivision are long since deceased.

This vague language and the age of most up-north and lake-side plats is extremely common in neighborhood disputes like these.

Even more unique, no parcel is adjacent to the water’s edge, which is traditionally the way for determining who has riparian or littoral rights. See 2000 Baum Family Trust v Babel, 488 Mich 136, 143 (2010) (owners of riparian land hold certain exclusive rights, including “the right to erect and

maintain docks, as well as to permanently anchor boats off the shore.”); see also Morse v Colitti, 896 NW2d 15, 22 (Mich Ct App 2016). (Full disclosure, this law office represents Mr. and Mrs. Colitti).

Therein lies the rub.

The trial court, in a spectacularly surprising decision, held that none of the lot owners have riparian rights. An appeal ensued.

From my point of view, if there had been no dedication, then the case would have been an easy one–the trial court would have been right in that none of the lots owners (unless they had a deed to the park) owned the property.

But it is never that easy.

The three judge panel correctly explained that “the interposition of a fee title between upland and water (i.e. the existence of someone else’s land) destroys riparian rights, or rather transfers them to the interposing owner.” However, Michigan law has created a slew of unclear exceptions to this rule, including for highways or a walking path. This is because attorneys for property owners closer to the water have tried to create more exceptions. In this case, there is a park.

The law on the interposing “park” is less than clear. The problem currently is that court cases keep going in different directions. Sometimes a panel of judges find that the existence of a park is similar to a walkway or highway, sometimes they do not.

The reason, I believe, this legal madness continues is because the courts never focus on the key issue–who owns the land abutting the lake. Attorneys for the lots owners closer to, but not on, the water conveniently “forget” that key point. Riparian rights run to the owner of the waterfront property, which can be shared with a whole neighborhood via a dedication or an easement. Moreover, prescriptive rights can come into play too.

In this case, the panel decided not to decide and sent it back for more argument in the trial court. Cases like these are important because the trial judge’s decision could literally destroy tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars of property value for the backlotters.

My advice to you (if you are in these kinds of legal fights) is do not hire a general practice attorney; get a riparian rights attorney who specializes in the nuanced understanding of Michigan water law.