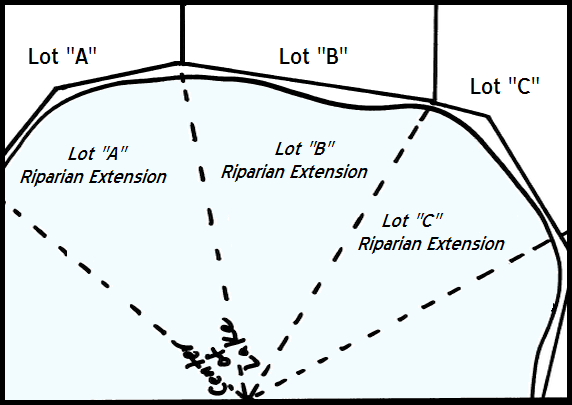

Ownership of riparian property automatically includes that portion of a lake’s bottomlands known as the riparian or littoral extension. This principle is well established under Michigan property law. A recent Michigan Court of Appeals decision reconfirms the same but added a further clarification.

In Devils Lake Ventures v Devils Lake Highway Ventures, the plaintiff purchased five acres of land abutting Devils Lake in Lenawee County. It brought a “quiet title” lawsuit contending that it acquired riparian or littoral rights to the bottomland property as part of its purchase of the upland property in 2014.

This would normally be an slam dunk case. With some unique exceptions, the title of the riparian owner follows the shoreline under what has been graphically called a “moveable freehold.” A deed or lease describing a parcel of land as running along the shore of a particular lake or watercourse automatically conveys to the center of the lake or the thread of the watercourse, even if the deed is silent.

In this case (not one of ours), the defendants argued that they owned the bottomlands of the lake pursuant to a federal land patent dating back to the nineteenth century, before Michigan achieved statehood, and that the language of the deeds for the abutting Semelka property did not convey any interest in the disputed bottomland portion.

The argument is not completely unfounded. As this law office has explained before, the navigable waters and its bottomlands of this state were, before statehood, part of the Northwest Territory of the United States created by the Congress of the Confederation of the United States in 1787, something many of us learned about in grade school. On January 11, 1805, the Territory of Michigan was established by an Act of the United States Congress, 2 Stat. 309 (1805). This was the first step to allow Michigan to become a formal state. Later in 1835, the first constitution of Michigan was drafted and was later ratified by the People of the Territory of Michigan on October 5-6, 1835 in anticipation of formal admission to statehood, which later occurred in 1837. The citizens of the forthcoming State of Michigan (i.e. the State) would be receiving title to the navigable waterways of their newly forming state. “The People of each State, based on principles of sovereignty, hold the absolute right to all their navigable-for-title waters and the soils under them, subject only to rights surrendered and powers granted by the Constitution to the Federal Government.”

However, if a piece of property had been conveyed by the federal government before statehood, that property could not have been given or conveyed to the citizens of Michigan upon statehood. In essence, pre-statehood deeded property still remained in the name of the prior buyer. And when the federal government conveyed property like this long ago, they were called “patents.”

In Devils Lake, the defendants argued that because the lake bottomland was originally conveyed by a federal land grant patent and the property was not submerged when the patent was issued, the trial court should not have resorted to state law regarding riparian and littoral rights.

Unique argument! However, it was rejected. According to the court, unless there are reservations or exceptions in the pertinent grant from the federal government, the laws of the state determine the extent and nature of the ownership of riparian proprietors. The title of a person claiming under a federal patent, which by its terms bounds the land on the margin of a body of water, extends beyond the edge of the lake or watercourse, the extension is by virtue of state law.

The take-away: the fact that the disputed bottomland property was originally part of a federal patent did not foreclose the court from applying Michigan’s law of riparian and littoral rights to determine what rights existed as to submerged bottomland property on an inland lake.